Jack served on H.M.S Vanguard in 1959. This video records the history of Vanguard and her retirement from the fleet.

IN THE BEGINNING

I remember very little of my early years. I was born in Dorking, Surrey, on 28 August 1932. I was the second child born to Ethel Frances and Edward Robert Hygate. Their eldest child, Doris Willette was born on 4 September 1924, so I had a “grown up” sister to keep an eye on me.

From all accounts I was a little horror as a child (although ‘little’ is not the adjective my mother would have used to describe me at my birth as I ‘weighed in’ at a little over ten pounds). We lived at No. 28. Rothes Road, Dorking and I have no real recollection of the house or of its surroundings.

I believe that family life was fairly relaxed, with annual holidays with friends and relatives. These holidays were spent mainly at seaside resorts, with Bognor Regis being a family favourite. This casual, relaxed existence continued until a family tragedy occurred. In 1935 my sister died of peritonitis, in very unfortunate circumstances when she was only ten years old. I think that the relationship between mum and dad was never the same after Doris’s death. Mum blamed dad for Doris’s death and I suppose that there was some justification for her feelings. Dad was a ‘disciple’ of Bernar McFadden (inasmuch as he had a whole set of ‘psuedo-medical tomes’ written by McFadden to which he constantly referred – even after the death of Doris). McFadden had a philosophy that suggested that the body, with the assistance of certain foodstuffs, exercises and compresses, etc., could cure itself of any known complaints. Unfortunately his ‘cure’ for appendicitis was to use cold compresses and consequently when Doris was diagnosed with appendicitis she was treated with cold compresses instead of being hospitalised. The obvious outcome was that the appendix burst and Doris died shortly afterwards in hospital. Mum was devastated. Doris was as near to perfection as anyone could come in mum’s eyes (and I have reason to believe that dad idolised her too). Probably my own destructive, noisy and uncooperative nature would have helped to enhance Doris’s status within my parent’s eyes. From the time Doris died, until I eventually left home, to get married, I recall being constantly aware of a lot of ‘Doris memorabilia’ – some tracts that she painted at Sunday school held pride of place in my bedroom. Mum had kept dolls, a doll’s house, school books, clothes, etc. I am sure that she would have constructed a ‘shrine’ had she been given the opportunity.

In the meantime I continued to be my usual horrible self (or at least that is what I was told). Certain unsavoury stories were recounted about this loud-mouthed (apparently the neighbours had nick-named me ‘Coke hammer” because of my loud and raucous voice) bad-tempered kid. One such story tells of how mum found me with her polished copper kettles happily filling them from the water flowing down the gutter outside 28 Rothes Road after a rainstorm. Mum collected her kettles, gave me a tongue-lashing and a healthy whack for my misdemeanours. I remained outside, feet in the gutter bawling (possibly more from having had the kettles removed than from the smacking), when a concerned clergyman came along and made the mistake of leaning over and asking me what was the matter? His reward for his concern? This ill-humoured, bawling brat (now in the middle of a full scale tantrum) struck out at him and sent his expensive, immaculate Homburg flying off into the gutter. I am informed that his comments as he retrieved his hat and continued on his way were unlikely to have been used in any of his future sermons.

These stories attributed to my nature during my early years I pass on as hearsay, although I have acquired enough comments from cousins and other relatives over the years to convince me that ‘I was not nice to know’! I am sure that others will come to mind as I continue recounting what I remember of my life.

When I was three we moved from Surrey to Devon. At this young age I had no idea what had prompted the move, although I suspect that dad having been promoted to the position of Quarry Manager for the company for which he worked. In hindsight I am sure that the move was very timely. Mum would have needed to get away from Rothes Road so that her tragic memories (which she was almost relishing) would have the opportunity to be lost in new experiences. And our new surroundings in the little village of Woodbury in South Devon provided plenty of new experiences, not the least of which was the lifestyle.

We initially boarded with a farming couple, Mr and Mrs Ted Ingleheart and Ted’s elderly mother. The Inglehearts owned a thatched cottage on the outskirts of the village of Woodbury. Woodbury was a small village with a general stores, a post office, a cafe, a souvenir and oddments shop, an old stone church and a village green. It was a little off the main road between Exmouth and Exeter, although about half of the Devon General buses running between Exmouth and Exeter used to deviate to pick up custom from Woodbury. The cottage that the Inglehearts owned would better be described as being in the country, rather than being on the outskirts of Woodbury, as there was only one other house in the lane and no houses within a mile. There was no running water, water was obtained by using a large wrought iron hand pump in a tiled pump/store room. The only toilet was outside (a lot of fun in winter; and don’t forget to take a bucket of water with you!). There was no gas or electricity, just oil lamps. Cooking was done on a massive old coal range (which Gran Ingleheart used to black-lead at least twice a week). The ‘pump room’ and the large kitchen had brown tiled floors and they always seemed to be wet.

There was a large yard at the back of the cottage where Ted Ingleheart used to keep his ferrets, a stack of rotting cider apples (he used to make his own rough cider) and some small farm implements. There was a large vegetable garden beside the cottage, running parallel to the country lane leading between the village and the common. At the end of the vegetable garden was a large hen run and chicken coop, holding about three dozen birds. Fruit, vegetables and eggs were plentiful during the growing (and laying seasons). Ted’s brother and his wife lived in a more modern house just beyond the garden and hen run and Ted used to keep his brother supplied with produce from his own small holding. Ted’s brother and his wife had a son about a year older than me, called Robin. Ted’s brother owned the paddocks (although we used to call them fields) on the other side of the lane and he was a dairy farmer, so we were never short of milk, cream and butter. Any milk which turned sour (a not uncommon event since there were no refrigerators and we always had more than enough milk) was turned into cottage cheese. Gran Ingleheart used to bake bread in the coal range in the form of the classic circular cottage loaf. Other supplies were obtained at the general stores (or by travelling to either Exmouth or Exeter). In this respect we were more fortunate than a lot of people as dad owned a car. He had owned a few cars before we went to Devon. I believe his real favourite had been a Trojan – because it had so few moving parts! The car we travelled to Devon in was a Wolseley ‘Hornet’. My only recollection of this car was one day when I was sitting in the passenger seat alongside dad and we were returning home. We were almost home and were approaching the gates of one of the farm houses, on the main road in Woodbury, about the time the farmer decided to move the cows from his yard back to the fields. As we came close to the gate a cow ran out – right into the path of dad’s car. The Wolseley ‘Hornet’ was a solidly built car, but it was no match for the side of the cow! We hit the cow, I hit the windscreen with my head and the cow fell down and the car came to an abrupt halt in a cloud of steam. The cow picked itself up and took off down the road. The farmer and dad started an argument as to who was to blame. The farmer was yelling at dad that ‘Rosie weren’t loikely to be giv’n any more milk fer zum toim to come an wot do ‘ee intend to do ’bout it?’ Dad wasn’t overly worried about the cow, particularly as it had got up and run off – something his car was unlikely to do! For my part I was administered to by a very tubby and cheery farmer’s wife, who was smearing pounds of butter onto the egg-sized bump on my forehead. Eventually tempers cooled and reason prevailed, but the poor old Wolseley ‘Hornet’ was towed (by the farmer’s tractor) to the village green. I assume that it was eventually picked up by a scrap merchant, but it sat on the green for a long time as a reminder to dad that, when it came to a collision with a farm animal, it was the car which normally suffered most damage!

Our stay with the Inglehearts was only for a few months. My recollection of that time is that it was a magnificent summer. On one such summer’s day I went with dad, the Ingleheart brothers and one or two other men to a neighbouring wheatfield. The wheat was to be harvested and the men were going there to shoot rabbits. The men took up their positions around the edge of a field as the harvester cut its way from the outer edge towards the centre of the wheat. The men were there with shotguns waiting for the rabbits to come running out of the wheat. To start with the shooting was slow, but as the area of wheat left to be cut diminished more and more rabbits broke cover and ran. When there was only a small area left to harvest, the rabbits that had been moving towards the centre of the wheat all broke cover together. The noise was incredible as half a dozen shotguns blazed away furiously. Ted Ingleheart and dad went back to the cottage triumphantly carrying over a dozen rabbits between them. It was Gran Ingleheart who took on the job of skinning and gutting the ‘trophies’. Actually, rabbit stew and rabbit pie became two of my favourite meals – but unfortunately rabbit later disappeared ‘off the menu’ with the introduction of myxamatosis after the war. I occasionally went with dad and Ted Ingleheart when Ted took his ferrets to catch some more rabbits for the table. It was not as exciting as the rabbit shoot and I was not very keen on the ferrets. They seemed only too willing to bite anything that they could reach and although they were his ferrets Ted was bitten quite a few times. One of the other disadvantages of using ferrets that you had to have a very good idea of the construction of the rabbit warren. Before you put a ferret down the hole you had to attach nets over all of the exits. If you had missed an exit you could guarantee that the rabbits knew which was the safe escape route. Half a dozen rabbits would come streaking out of the hole that had been overlooked, closely followed by the ferret in ‘hot pursuit’! The chances of catching the ferret weren’t particularly good. Another disadvantage was that occasionally the ferret would be quick enough to catch and kill a rabbit underground. You then had to wait ages for the well fed ferret to reappear (sometimes, after an underground feast, the ferret would decide to take a siesta and then you really had a long wait).

I have no clear picture of what mum did with her time during our stay in Woodbury. I know that I used to accompany her when she went ‘shopping’ at the village store. She must have done all of the letter writing. Every trip to the village store entailed a slight deviation to the Post Office (next door – and I suspect all part of the village stores as it was ‘manned’ by the grocer’s wife). There mum would post a hand full of letters to relatives in London and Crawley and friends and neighbours from Dorking. There were usually plenty of replies and the postman, whom I am sure had seldom ever had to stop at the Ingleheart’s before, must have been thinking of applying for a salary increase! I have one clear memory of mum at this time. It was a beautifully warm and calm summer’s. Mum was sitting in the dining room (we had just finished the midday meal) when a wasp decided to join us. Mum had no love for wasps and picked up a rolled-up newspaper and waited for the wasp to settle. It eventually alighted on one of the windows (these windows had a sort of swirl pattern moulded into them and were becoming quite rare except for very old thatched cottages). Mum seized her opportunity and swotted the wasp savagely with the rolled-up newspaper. It was just unfortunate that there was a dessert spoon wrapped up inside this home-made fly-swat. It took us quite a while to gather up all of the shards of glass laying about the path and flower garden! (When I stopped outside of the old cottage, whilst on a visit ‘home’ in July 1995, I was disappointed to see that the thatched roof had been replaced by tiles and amused to see that there was still a plain glass window pane amongst the panes with the swirl pattern).

After a few weeks dad bought another car (an Austin 12, registration plate AJJ 73) and rented a house on the outskirts of Exmouth and we moved to our new home.

The house we rented was a semi-detached two storey brick house on the main road from Exmouth to Exeter at an area known as Courtlands Cross. It had three bedrooms (two double and one single) and a bathroom/toilet upstairs and an entrance hall, lounge (front room), dining room, kitchen (with walk in pantry), coal cellar and toilet downstairs. There was a wooden garage at the end of an unsealed drive. The houses this far out of town were not on the sewer system so, at the bottom of the garden was an underground septic tank. The contents of the tank (and the others down the road) were pumped into drainage ditches dug into the sloping field at the back of the house. There was only one other semi-detached house and a garage/service station between us and the lane which marked the boundary for Exmouth. The house was called “Tor View” and had a very pleasant view over the fields of Sir Garbut Knotts’ estate, the wide estuary of the river Exe, the village of Starcross on the other side of the river and behind Starcross the Haldon Hills. On the town side of our house there was an empty space before the next row of houses. This space opened out onto the large field on the river side of the house and consequently we were often visited by cows that had been turned out to graze. Fortunately none of them ever felt the urge to test the flimsy wire fence separating us from them (although they used to enjoy eating the next door neighbour’s hedge). The neighbour was a fairly cantankerous old codger and he used to try to drive the cows off by throwing stones at them. He didn’t take too kindly to the four-year old brat admonishing him for his actions and informing him that ‘they aren’t your cows’. This verbal exchange was reported to my father but dad decided it wasn’t worth getting too serious about, so I only got a lecture on respecting my elders. Our next door neighbour on the other side was Joe Howes. Joe quite often came over in the evening to play cribbage with dad. Joe was an old man who was looked after by his live-in daughter. He was quite a gardener and I think his vegetable garden more or less forced dad to do quite a bit of gardening, but I don’t think it was dad’s favourite occupation. Dad tended to put a large percentage of the garden into potatoes. I think that he reasoned that they didn’t need so much attention as other crops!

Because dad was manager of a stone quarry (The Blackhill Stone Co. on Woodbury Common) and was supplying roading contractors with various sizes of screened shingle, it wasn’t long before we had a properly sealed drive. Some large roughly egg-shaped stones (about 12″ – 18″ in diameter) were accumulated over a few weeks and an impressive rockery/retaining wall was constructed between the drive and the front lawn. Mum was none too pleased with the indoor coal cellar. It had its advantages that you didn’t have to go outside on freezing cold, wet nights to fill the scuttle – but it also had the disadvantage that coal dust always seemed to permeate throughout the house, and even more so when Tom Phillips, the coal merchant, delivered the coal!! A large wooden coal-bin was constructed behind the garage and the indoor coal cellar eventually became a storage room. During the summer months the outside coal-bin became a handy hiding place for when I had committed some misdemeanour or other. Needless to say my ‘secret hideaway’ didn’t remain secret for very long, (the coal-bin then doubled as an imaginary fort, a house, a ship and numerous other objects depending upon whatever game we were playing at the time).

When we first moved to “Tor View” there were very few other children in the group of houses leading up to Courtlands Cross. I can only recall three other children, Raymond Heyde and John Kemp, both older than I, and Janet Coombs who lived two houses away and was about my age. Unfortunately Janet’s parents were both teachers (at what was known in those days as the Senior School) and Mrs Coombs decided that she couldn’t stand my accent (which I believe was a kind of hybrid cockney gleaned, no doubt, from mum). I used to have elocution lessons from Mrs Coombs. Once, when my Uncle Tim was staying with us, he seemed to derive some humour from my early-age elocution lessons. Uncle Tim, Aunt Lil and cousin Douglas used to regularly come down from Peckham to spend their summer holidays with us. During one of their early visits I came in for lunch after one of my ‘lessons’ and Uncle Tim wanted to know what I had learned. I carefully recalled my set lines – “How now, brown cow; grazing in the green, green grass”. No doubt my enunciation was rather exaggerated and Tim was obviously amused and enquired as to whether, at the completion of the lesson, I had said “See yer ‘s’arternoon, arftr’av’ad me dinner” before coming home. I suppose I was contemplating using this form of farewell, when I received a withering look from mum and advised it would not be good for my health to try it! I guess Janet Coombs and I never became very friendly, I was naturally overawed by her parents. I was always invited to her birthday parties (and out of duty I returned the compliment) but I never enjoyed going. In fact I rapidly developed an aversion to going to all parties (including my own), which appears to have lasted the rest of my life.

Eventually two other families moved into Courtlands Cross, the Scullards and the Partridges. The Scullards had two boys about my age, Jim and Richard, and the Partridges had a daughter, Noreena.

Having some ‘playmates’ around my own age was probably very timely. I had become very ‘insular’, hardly ever doing anything without either my mother or my father being there. At least now I was playing ‘away from home’ – even if it wasn’t very far from home. I say that this was timely, because I was approaching my fifth birthday and school was just over the horizon. I dread to think what school would have been like if I had never ever left mum’s apron strings before having to spend a whole day outside of her ‘protective shield’.

For a few weeks before I was to go to school both mum and dad spent a lot of time ‘indoctrinating’ me about what school was all about and what life at school was like. I am sure they both knew that my raucous ‘coke-hammer’ voice and apparently belligerent ways were an extremely thin veneer and that underneath I was more nervous than a neurotic kitten. I think that the well meant tête-à-têtes probably did little to reassure me, but they tried. When the great day arrived for me to start school, mum walked me the one and a half miles from home to the Exeter Road Infant’s School. She introduced me to the Headmistress, Miss Long, saw me safely settled in to my classroom, gave me my paper bag with the jam sandwiches oozing through it and departed. I remember nothing at all about that first morning except that I kept myself very much to myself, didn’t mix with any of the other kids at playtime (although they all seemed to be having fun!) and instead ate my sticky sandwiches. When the bell sounded for the lunch break, I left the classroom, left the school and walked the one and a half miles back home. Mum was horrified when I arrived indoors, her first reaction was that I had been sent home sick and asked me what was wrong. I replied that nothing was wrong and that I had been to school, so now I had come home. In all of the pre-school discussions no-one had told me that school was an on going event and that you didn’t get it over with in one morning!! Needless to say I was less than impressed when I got hauled off to school again the next morning. I was even more distressed the following week when mum decided that I would benefit from having a hot meal at midday (in those days most people had their main meal in the middle of the day – only the ‘landed gentry’ ate their main meal at night). I was therefore enrolled for school dinners. I was probably the ‘fussiest eater’ ever to draw breath, there were so many things that mum no longer bothered putting on my plate. I wouldn’t eat cabbage, swede, turnips, spinach, broccoli, onions, mutton, fatty meat, gristly meat – the list was endless! I think that the way cabbage was cooked in those days put me off cabbage for life. The standard method of cooking cabbage then was to boil the cabbage for a long time. The cabbage and the water in which it had been boiled were decanted into a colander to allow the water to drain away (taking any goodness with it) and the remaining soggy mass was squeezed into the colander (with a very large wooden ‘mushroom’), thereby ensuring any residual flavour and goodness was consigned to the sink! The resulting compacted mass was then cut into blocks and dished out with the rest of the meal. Imagine my horror the first day that I attended for school dinners to discover that you were expected to eat everything on the plate! That first school dinner turned out to be mashed potatoes, sausages and boiled swede. Something approaching panic gripped me as I moved up the queue, clutching the plate onto which the kitchen staff were going to dispense the various components of the meal. God smiled on me that day. As I moved along the table the staff member in charge of the boiled swede missed me out! I couldn’t believe my luck. My good fortune didn’t continue beyond that first day. For the following two weeks I forced down the foul tasting contents on my plate, before finally convincing mum that I would far rather crawl home and back in a howling blizzard that be subjected to further gastronomical torture. One incident at school dinners really convinced me that I had to talk mum into letting me eat at home. One day the boy that I was sitting next to put up his hand to attract the attention of the supervising mistress.

“Yes dear” she said when she came up to him, “is there something wrong?”

“Please miss, there’s a caterpillar on my cabbage.” The mistress (and I) inspected his dinner, causing me to feel decidedly nauseous!

“It’s alright dear,” she said “you don’t have to eat it.” With a look of relief on his face he pushed his plate away.

“No dear,” she admonished, “I mean that you don’t have to eat the caterpillar.”

That did it for me. The thought of not only struggling to force down soggy cabbage, which I hated at the best of times, but at the same time having to negotiate my way around a large, juicy caterpillar was more than I could envisage. It wasn’t easy to convince mum of my worries at this time as she was almost ready to produce the next member of the Hygate tribe, but at five years old I was totally ignorant of her condition and the caterpillar incident had made me very determined to get my way. Dad did the catering whilst mum was in the nursing home having Brian. It is debatable as to which was the worse, dad’s cooking or school dinners!

The arrival of Brian was, I think, a disappointment for mum, who desperately wanted another ‘Doris’. For the first two or three years of his life mum used to make believe he was the daughter she had so wanted and she used to dress him as a girl. I was too young still to appreciate what was going on, although I was observant enough to know that something wasn’t what I would have called ‘right’. I am sure that those first years didn’t have any lasting effect on Brian – although it may explain why he hangs on to the scruffy beard he has worn for long periods of his adult life!

The arrival of my kid brother had little or no effect on my life at the time. I continued going to and from the Infant’s School twice a day and I slowly widened my circle of friends (although only three of them lived fairly close to our house). One of my new friends was a Muriel Thorn, who’s father owned Backenhayes Farm (less than a mile from where we lived). This friendship extended through to both families and as a result we quite often used to go out, as a family, to spend the day at Backenhayes farm. Dad was back into rabbit shooting and trapping (although mum was never all that keen on skinning and gutting the results of his success) and we all became involved in such country pastimes as churning butter, haymaking, haystacking and making wheat sheaves and so on. I particularly liked the haystacking because I got to use a pitchfork (and although it was home made, small and the tines were very blunt the real workers gave me a wide berth). I also got my own stone jar of farmhouse cider to drink with my ‘ploughman’s lunch’ (except that my stone jar contained a fizzy orange drink called Corona). The adult workers always seemed to be a lot happier during the afternoon than they had been in the morning!

Other kids I got to know through school, and who didn’t live too far away, included Fred Penhaligan and Hazel Payne. Fred was the son of the estate manager for Sir Garbut Knotts’ estate. He was a quiet kid and I don’t think that we ever built up much in the way of a strong friendship. Hazel Payne used to live in the ‘last house on the right’ at Halsdon Cross and our friendship was really just the companionship of two young kids walking to and from school together. Robin Ingleheart, Ted Ingleheart’s nephew, used to sometimes get the bus from Woodbury and we would spend the day playing in the field behind our house. We played all the usual games like ‘Cowboys and Indians’ and used to fly kites (made by dad). Dad could never make a plain, simple kite, it had to be a feat of engineering. The box kite he made me seemed to take forever to make (it was probably only a day or two) and was so heavy I couldn’t’ imagine how I was going to be able to launch it. Eventually, Robin and I, working together got the kite airborne. To dad’s credit it was an outstanding success. There was enough string on the line to have nearly reached Mars and we certainly got the kite to an impressive altitude (well, it looked very, very small at the end of the line!) In those days we didn’t have to worry about getting entangled with low flying aircraft, you hardly ever saw an aircraft. Those we did see would have looked quite out of place nowadays – especially the occasional Autogiro (a sort of helicopter with fixed wings). There was one draw back with dad’s successful kite – the fun of kite-flying rapidly dissipated when it came to reeling the thing in – it seemed to take for ever and your wrists were aching and throbbing by the time it had finally been retrieved. Kid’s memories were notoriously short and the next time that the wind was right we would try to get it even higher. We even added more line on to the ‘reel’ (the short length of broom handle around which the line was wound in a figure-of-eight motion. Our continued attempts to beat previous ‘altitude records’ were ultimately the cause of our downfall. We obviously hadn’t been too careful when tying the knots to add extra line to the reel and, sure enough, on one windy day we had got the kite really flying high when suddenly the effort required to restrain the kite vanished! The kite was free!! I have no idea where it eventually came to earth, but somewhere in the English Channel would probably be as good a guess as any.

Another of dad’s masterpieces was a sledge (or sleigh if you prefer). We had had a substantial fall of snow followed by some frosty nights and more snow. The field behind the house seemed to be the ideal place for tobogganing, so dad put together a pretty basic wooden sledge. It wasn’t successful from the top of the field, but part of the way down the hill the slope was appreciably steeper. From this starting point it was reasonably successful. However…..

The next modification was to make the wooden runners narrower. This was a failure. Immediately two 2″ wide steel runners were affixed to the bottom of the wooden runners. It made the sledge very heavy, but, once the snow had polished these runners, it really zoomed over the snow. After one frosty night the sledge actually worked faultlessly from the top of the hill. Again the new found advantages of the longer run were counteracted by the long drag back up to the top again. I have no difficulty in understanding why ski lifts are so essential on ski fields – I wish there had been a ‘sledge lift’ on ‘our’ field. Perhaps dad would have made one if I had asked!

Other ‘toys’ that dad produced included a pea-shooter (which was, in fact, a boiler gauge glass), it was also very accurate. I think that, at first, mum was worried that I would fall over with it in my hand a give myself a nasty gash. Surprisingly that didn’t happen. I say surprisingly, because I always seemed to be falling over and having mum ‘dab’ my grazed knees an elbows with copious quantities of Iodine. And yes, it did sting!! My ammunition, as with all pea-shooters was dried peas – although some kids used to use small pebbles. Another ‘toy’ was a catapult (or slingshot). I had come down from my bedroom early in the morning before anybody else was up. I found the catapult in one of the sideboard drawers – but what did I use for ammunition? No, I didn’t use dried peas, I used a marble!! I drew the elastic back (fortunately only a short distance) and released the ‘missile’. The marble hit the glass in the left hand French door. Almost scared to breathe I tip-toed to the window praying that I had done no damage. No such luck!! The impact had knocked a butterfly-shaped piece of glass (about an inch wide) from the outside of the glass. Apart from a minute hole the internal surface of the glass; the damage, which I hoped would be viewed as tolerably minor, was all on the outside surface. I put the catapult back in the drawer, the marble back in its bag and me back into my bed. It was nearly two weeks before the damage was noticed. In those two weeks I felt that the Sword of Damocles was poised over my head. Amazingly I immediately admitted to being the perpetrator of the crime. Dad wanted to know how I had done it. When I explained what I had done on that morning he didn’t believe me, because the damage was on the outside and he insisted that I must have been outside. I don’t know whether he had engaged in some amateur research during the morning at the quarry, or whether he had just asked around, but by dinner time he was convinced. The amazing thing, as far as I was concerned, was that dad was more interested in the physics involved in the way glass breaks that he forgot to punish me in any way! It was a very long time before I ever picked up a catapult again!!

H.M.S. DIAMOND

Reading your letter I was staggered to realise how similar our first 12 years of service had been. After returning from the ‘extended leave’ we had earned (to enable us to spend that massive Korean gratuity they had given us) I managed only a few days in the Tiffy’s Mess in Chatham Barracks before collecting a ‘pierhead jump’ to H.M.S.Diamond. At the time I was told by the Movements Office that the Diamond was at Portland and that I was to join her there – and to make my journey from Chatham to Portland more enjoyable and relaxed (no doubt to overcome my trauma at getting an ‘instant’ posting) I was to take charge of a group of seamen and stokers who were to take passage to the Mediterranean on the “Loch Inch”. As always when things look as though someone has dealt you a lousy hand it got worse. As we left Barracks in the back of a truck en route to the railway station the heavens opened – and it hosed down. By the time I had got this motley bunch on to the train (surprisingly with all of their gear, kitbags, hammock, etc intact) we were all soaking wet and nobody was very happy. Changing trains in London was a disaster. All this lot wanted to do was to find a boozer and to spend the rest of their lives in it. I gained the distinct impression that this lot were not keen on their respective draft chits. I have no idea what ship, or ships, they were joining – but I had a feeling that they were not destined to be ‘happy ships’. Anyway, we eventually got to Portland and (of course) discovered that nobody had thought to lay any transport on to get us from the station to the “Loch Inch”. We struggled through the rain, which was now of the steady soaking variety, carrying kitbags, cases, hammocks (and in my case, a heavy toolbox, from which I had fortunately lost a lot of tools or it would have been even heavier). By the time I had got this, by now, mutinous rabble to the gangway of the “Loch Inch” I was feeling less than sociable. Having completed the first part of my duties I looked around for the Diamond. Since Portland is not the largest naval base in the world I had the impression that finding a Daring-class destroyer shouldn’t prove too difficult. Having failed in my initial scan of the territory to see this ship I eventually did the obvious and asked a bedraggled nondescript official where I would find the Diamond. “Dunno mate” was the reply “she went through here a couple of days ago on the way to the Med – she didn’t stop!” I now went from feeling antisocial to feeling positively murderous. If the Movements Office had got its a*** into gear I could have joined the ship in Chatham and saved me a day’s agony and if the same Movements Office had known anything at all about the Diamond they would not have sent me to join it where it hadn’t even called in!! In my extremely black mood I picked up all of my gear, marched off to the “Loch Inch” and walked aboard. I was of course challenged at the head of the gangway as to who I was and what I thought I was doing. I replied that I was E.R.A.Hygate taking passage on the “Loch Inch” to Malta to join H.M.S.Diamond. “You ain’t on my list mate” this officious Petty Officer informed me. I told him that I couldn’t give a stuff about his list and if he was going to take the responsibility for sending me back to Chatham would he please get a move on and organise my travel warrants etc. He decided that that sounded like too much paperwork (apart from being far beyond his intellectual capabilities) so he told me to report to the Chief Tiffy. So I took ‘unofficial’ passage to Malta and discovered on my arrival that the Diamond wasn’t there either!! I invited myself to spend a week in H.M.S. Ricasoli (Fort Zenderneuf) until the Diamond returned from sea. I enjoyed that week – nobody knew what to do with me so I spent all day, every day, swimming and lazing around the Fleet Lido drinking Pepsi Cola. So we both served on Daring class destroyers (although we were leader of the 5th Cruiser Squadron – consisting of Diamond, Dainty, Duchess and Decoy). Why they decided to call us ‘cruisers’ only some pen pusher at ‘Our Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty will ever know – I don’t think that any foreign powers were fooled.

I enjoyed my eighteen months on the Diamond, she really was a happy ship and the Tiff’s Mess was probably one of the happiest messes on board into the bargain.

I.C.E. COURSE

After leaving the Diamond, Edgar and I got ‘drafted’ to the Diesel Course. I can’t say that I enjoyed the course and the Mess President was a total pillock – if you don’t believe me ask Edgar. I think they carried on a war of attrition for the duration of the course. At the end of the course we were interviewed by the Engineer Commander in charge? of the course in reverse order to our exam results. I had actually done very well in the exam and if I wasn’t top of the class I was certainly up there somewhere – consequently when I went in for my interview the Commander (E) had obviously decided that he was going to hear nothing but superlatives about ‘his’ course. I was told that the interview was totally informal, that I could and should say exactly what I felt and that nothing said would go ‘beyond these four walls’. “So, what did you think of the course, Chief?” he beamed. “Utter bloody rubbish!” I replied – and the atmosphere (which had been all friendly and light) suddenly took on a somewhat darker shade. “Explain yourself!!” he growled. I noted the absence of “Chief” and decided that we were now on a strictly formal basis with no room whatsoever for levity. I pointed out that I had no argument with the theoretical side of the course, but that there had been far to little practical workshop and actual engine experience. That I felt that if confronted with a diesel engine which was malfunctioning (or wouldn’t start) I would possibly eventually track down the problem with a series of eliminations, but that I felt that what the Navy really needed was someone who was so familiar with diesels and their associated problems that problem-solving became second nature. The Commander (E) was not impressed with my response (and come to that I think that he had ‘gone off’ me as well). I was dismissed, with a fair display of bad grace and thought nothing more about it – until I saw the comments written on my papers stating the I was not to be considered for service with diesel engines!! I wasn’t overly worried as I wasn’t thinking of volunteering for subs. anyway. And just to prove that the comments written on one’s papers are read and understood by those who ‘need to know’ I was drafted to H.M.S. Wildfire at Sheerness to oversee repairs and maintenance on Coastal Minesweepers!!

THE PRE-WAR YEARS

The years spent at “Tor View” up to the start of World War II sit in my memory as some of the happiest times of my life. Obviously memory mellows as the years pass by and this probably explains why the summers seemed sunnier, warmer and longer than any summers since. During these summers there were plenty of visits from relatives and we quite often visited mum’s relatives in London and dad’s relatives in Crawley. The London relatives always arrived by train and it was always exciting to meet them off the train as it steamed slowly into the station at Exmouth. By placing a penny into a dispensing machine by the platforms one could purchase a ‘platform ticket’. This enabled the owner to actually stand on the platform to meet their guests off the train. I used to pester my parents to purchase these tickets to satisfy my impatience to meet up with my aunts and uncles at the earliest possible moment – after all, they always brought me a present! I confess that I really enjoyed receiving presents as a child, something that I seem to have successfully repressed nowadays, to the point I find it almost embarrassing to be given a present.

Because we had so many visits from our ‘townie relatives’ during the summer months, a great deal of my school summer holidays and weekends were spent on the beach. If dad was able to join us we would pile into the Austin 12 and head off to either Sandy Bay (my favourite) or Ladram Bay. If dad wasn’t with us we would use the bus and spend the day on Exmouth Beach. As Exmouth was a very popular seaside resort, finding a space on Exmouth Beach was not always very easy. Finding enough space to erect three or four deck chairs was almost impossible. However, Exmouth had a long beach (the distance from the Pier to Orcambe Point must have been more than a mile), so you could usually find somewhere to ‘set up’ for the day. In those days there were ice-cream vendors plying their trade up and down the beach all day. Like newspaper boys they used to have loud (almost unintelligible) slogans that they called out to attract custom. I can still hear and visualise the Walls Ice Cream seller, in his white coat and white and blue peaked cap, yelling out,

“Walls ices!! Walls ices!! Keeps your blood in order!! Stop me and buy one!”

Unless he had very recently replenished his stock, when you bought an ice cream it had melted almost to the point of being liquid. All of his stock was kept in an insulated cube-shaped container with a small lid on top; he carried this ‘ice-box’ on a strap around his neck. Needless to say the inside of the container warmed up every time he opened the lid to make a sale. Walls actually also had a mechanised version. It was a larger insulated cube mounted over the front wheel of a bicycle – the slogan was the same though. From memory there was only one other proprietary brand of ice cream, and that was Lyons, but I don’t ever remember them selling their ice creams from anywhere other than shops. The ice creams were either ‘wafers’ or ‘cornets’. The wafers came in the form of a slab of ice cream wrapped in paper and two waffle biscuits, you carefully unwrapped the ice cream (trying not to drop it or get covered with it) and putting the waffle biscuits, or wafers, on each side. As a kid I used to enjoy squeezing the wafers and licking the ice cream from around the edges – the only disadvantage with this method was that the crisp wafers were a soggy mess by the time you had finished the contents and not particularly pleasant to eat. The cornets were formed by removing the outer wrapping from a flat cylinder of ice cream and pushing it into the mouth of a waffle cone. We could make a lovely mess with those by biting the bottom off the cone and trying to suck the ice cream through! This possibly explains why I was never allowed to eat ice cream in the car. Like most young children I was a great fan of ice creams, but the ones that I really used to like were purchased in Fortes Cafe (at the end of The Parade and facing The Strand Gardens). On the occasions that my Aunts or Uncles took me in there for a treat I used to get a ‘Knickerbocker Glory’. It was a very tall glass filled with ice cream and nuts and various ice cream syrups. To eat this mountainous quantity of ice cream required a very long handled spoon (and an inordinate love of ice cream). Perhaps it was just as well that these ‘treats’ were few and far between as I tended to be on the chubby side anyway. It was much healthier for me to get my treats on the beach where I could run, dig or swim of the excess calories!

Sandy Bay was not like Exmouth beach. It was more difficult to get to, unless you owned a car. Because of its relative isolation the expanse of sand was nothing like as crowded. To get to the beach you had to climb down some steps and a fairly steep path. This access came out at one end of the beach and as you moved further down the beach the impression of ‘isolation’ grew greater. It appeared as though the beach was between the sea and an unscalable cliff. This cliff behind the beach acted as a shelter belt, or wind break, so it tended always to seem like a warm and calm day when you were there. There were other advantages to this stretch of beach. It was very shallow, with no rips or currents, and therefore fairly safe for young kids. I actually learned to swim at Sandy Bay (after first having learned how to do ‘a dead man’s float’, which I used to practice at home on bath nights). For a very modest fee you could hire a ‘float’. These were made up of two long, hollow canoe-shaped floats, joined by two flat boards. Each of the hollow floats had a wooden bung at the top so that any water which had seeped in could be drained (but not at sea!). I used to enjoy going out with dad on one of these floats – the water was always so clear that you could see the sandy bottom although being in quite deep water. I used to enjoy looking at fish, seaweed, the occasional rock and some times at the turn of the tide you could see prawns slowly moving towards the shallow rocks inshore. Needless to say I had a ‘shrimp net’ and on rare occasions caught enough prawns to make an extra treat for tea (the bread and butter meal most people had about five at night).

Ladram Bay was not in the same class as Sandy Bay and I was never all that keen on going there. It had a similar access to Sandy Bay and it had floats for hire, but there the similarities ended. Ladram Bay was a pebble beach and a quite steep one at that. The beach was quite narrow especially at high tide during them spring tides. If you were an accomplished swimmer then I guess Ladram Bay was the spot. The beach shelved so steeply that the average person would be ‘out of their depth’ a mere ten yards or so from the beach. I know that dad enjoyed Ladram Bay as he did quite a lot of swimming and mum quite liked it ‘because you didn’t get sand in the sandwiches’.

Apart from the beaches, our summertime guests used to go for walks on Woodbury common (usually making the exercise worthwhile by picking blackberries if it was the right time of year). Sometimes they would hire a rowing boat at the village of Lympstone (about a mile from where we lived) and either go rowing or fishing on the River Exe. (There were also plenty of launches plying ‘Trips Around The Bay’ from the Exmouth seafront, but they tended to be crowded, noisy and expensive). Early on Sunday mornings during the season our coalman, Tom Phillips, used to run a fishing trip for a ‘chosen few’. We obviously must have paid our coal bills, as we seemed to spend a high percentage of Sunday mornings fishing. Our London relatives used to really look forward to these early morning outings and I was allowed to come along as ‘the boat’s mascot’! Funnily enough I always seemed to catch more than my fair share of mackerel. I really moved up in the ‘mascot stakes’ on one Sunday trip. We had been fishing, without any luck, for about two hours and it was becoming obvious that the concensus was for packing up and going home. At that moment I hooked and landed a mackerel! Tom Phillips carved a “J” on the tail and announced that ‘our mascot has found a shoal’. From then on mackerel were queuing up to commit suicide and the fishing again became boring, for a very different reason! Sunday tea after these fishing trips was always soused mackerel (and I have always felt the need to have vinegar with my fish ever since). As rabbit pie and rabbit stew were two of my favourite dinners, soused mackerel (and prawns) were my favourite teas. Perhaps it was the ‘hunter’ in me that made ‘self caught’ food taste better – or was it because it was so fresh and you knew where it had come from. My grandmother, on mum’s side (Emma Constable), would never buy a rabbit in a butcher’s shop unless it still had the fur on. She was convinced that in London butcheries skinned rabbit was more often than not skinned cat. She actually questioned our local butcher, Lloyd Maunder, as to whether his rabbits were cats!! It took all of mum’s tact and diplomacy to calm that situation down. We were never top favourites with Lloyd Maunder’s after that and that didn’t do us much good during the savage rationing days that were ‘just around the corner’.

Being a seaside resort there was always plenty of entertainment for the ‘townie visitors’. There were entertainments on the Exmouth Pier from a Helter-Skelter, Dodgems, Shooting galleries and an amusement arcade full of pin-ball machines. Uncle Tim was an absolute sucker for pin-ball machines, but the machine which put the greatest strain on his pocket was a ‘mechanical grab’. This was a grab crane that the player controlled with a couple of handles. The idea was to attempt to ‘line the grab up’ over a prize and hope that the jaws will lock sufficiently around the prize to enable the player to manoeuvre the object over a chute which delivered your hard earned winnings to the outside of the machine. The base of the grab was covered with cheap little sweets and if nothing else you could usually win two or three of these tasteless little jubes. The only item of any value that I remember Uncle Tim winning was a little travelling clock, the surround of which chipped quite badly as the grab dropped it from a great height into the chute!!

Besides the Pier there was always at least one ‘Fair’ would come to town. They always set up the fair on the King George grounds near the Devon General bus terminal. Dad was the member of the family who enjoyed the fairground rides more than the rest of us. I always ended up getting horribly dizzy and on the verge of throwing up after a few revolutions. I think that my worst experience was when dad took me onto a ride called ‘The Giant Waltzer’ at a fairground in Exeter. The Giant Waltzer consisted of about ten circular ‘cars’ each of which revolved around its own centre – at the same time, the base on which the cars were mounted went up and down slopes as it, in turn revolved around the centre of the ‘ride’. I don’t know whether dad had made some smart comment to one of the attendants or not, but as soon as the mechanism started to rotate this attendant decided to keep giving our car a savage spin. What with the spinning motion of the car, coupled with the up and down circular motion of the total ‘ride’, I felt very, very ill. I kept pleading with dad to get them to stop, but dad was not going to let some pip-squeak of a fairground attendant get the better of him!!! I was carried off of the ride when it eventually came to rest and mum walked me to the car and I took no further interest in the evening’s amusements. I enjoyed the dodgems and quite liked the ‘Big Wheel’, as long as I was accompanied. Otherwise I used to stick very much to the innocuous amusements, like ‘rolling the penny’ (where you rolled a penny down a slotted chute onto a table marked off in a series of squares with values marked in them). The idea was to try to get the coin to come to rest in the centre of one of the squares – and preferably one with gave you a healthy return, such as a shilling rather than just your penny back!! Needless to say that in the unlikely event of your coin landing up in a worthwhile square, the stall-holders eyesight improved to the point that he could see that your coin was actually clipping one of the four lines in the square – even when you were considerably closer to the coin than he was. They were not averse to jolting the table if it looked as though a coin was going to settle as a winner!! In those days travelling fairs used to include visual freaks for the visiting public to gawk at. The world’s fattest lady, waddling around looking like a flabby version of the Michelin tyre advert. There were tattooed ladies, wild men from Borneo, the elastic man (who used to tie himself in knots), bearded ladies – the list was endless, and I seldom ever went into the ‘booths’ that housed a particular ‘freak’. The photographs outside the booths were enough to turn my stomach, there was no way I could have looked at the real person. Even at that age I was sure that this was wrong – but I guess that it was the only way they could make a living and perhaps it was a step removed from street begging, but it wasn’t for me!!

The other entertainment that used to come to town was the circus. The ‘Big Top’ was nearly always erected in the field at the bottom of the road (on the opposite side to our house). I wasn’t keen on circuses either (I was a very difficult child to amuse). I quite liked the clowns, I could tolerate the performing horses, but people climbing into the lion’s or the tiger’s cage were viewed by me through clenched fists and closed eyes. It was a waste of money taking me to the circus, but relatives always seemed to think that treating me to a trip to the circus was mandatory as soon as the circus parade appeared outside our house heading for town. Keen gardeners were ready with buckets and spades to scoop up the droppings from elephants, etc. Fortunately dad seemed to be a bit ‘slow off the mark’. As far as I can remember Exmouth was spared any ‘excitement’ brought about by any escaping animals – none that were dangerous, anyway.

Other summer pastimes could be quite boring to a young lad. Once a year we would all head out into the fields to pick dandelion heads (heads only, no stems or leaves). Between us we picked enormous quantities of these flower heads (my contribution was usually fairly minimal) and then mum, with some assistance from dad, would put the lot into a large crockpot, which lived on the back porch, add various ingredients such as water, sugar and yeast. This eventually used to produce many bottles of dandelion wine and from all accounts had a kick like a mule. Dad used to also make elderberry wine. Later on in his life he made wines from just about anything and I have been reliably informed that they ranged from barely palatable to extremely enjoyable (although I seldom got the opportunity to taste many of them).

In the winter we seldom, if ever, had visitors. Instead there used to be a lot of parties around the Christmas and New Year period. These were ‘grown up’ parties as opposed to kid’s parties. In those days a party was usually a light evening meal, followed by some drinks and some conversation and then there were ‘games’. They played games such as ‘Beetle’, ‘Post Office’ (nothing to do with Postman’s Knock), Monopoly, card games such as ‘Beat Your Neighbour Out of Doors’, ‘Happy Families’ and so on. Sometimes they would play records on our enormous radiogram (dad’s pride and joy) and endeavour to dance. The dancing was seldom a success due to the lack of space and the carpet on the floor. The carpet square in our dining room was so tatty by this stage that you could have done yourself a mischief by tripping over the frayed areas!! There were also some games which involved ‘forfeits’. Forfeits were penalties that were awarded for failing in a game, or some other misdemeanour. At my tender age (I was around five or six) I couldn’t understand why ‘grown ups’ found it so funny to embarrass each other by imposing silly things for them to do, when they were supposed to be having fun. But I guess that as a child I was a pretty timid. I was sometimes allowed to join in some of the games in the early part of the evening and I quite liked playing ‘Beetle’. I am sure that nowadays such a game would not appear on the agenda of an adult party. In ‘Beetle’, each player took it in turns to throw a dice. Each face of the dice was related to a part of the beetle’s anatomy. The body of the beetle required the player to throw a ‘six’ and until you threw a six you could not start. Once you had thrown a six and drawn in the body, a ‘five’ let you draw the head, the eyes were represented by the ‘four’, the legs were ‘two’ and so on. You, of course, could not draw in the beetles eyes or antennae until your beetle had a head – but you could add legs and a tail to your headless beetle if you threw the correct numbers. The first player to complete his or her beetle was awarded bonus points on top of the 33 points for the total beetle – the remaining players added up the total value of points for their incompleted insect and these became the scores for that round. The game then resumed until the next round’s winner was found and so on. The player with the most number of points at the end of the game (usually 12 rounds of ‘Beetle’) was declared the winner. I think most people got their enjoyment from the artistic effort they put into drawing their beetles and even as a kid I could see that some adults had distinctively humorous artistic talents! The incredible thing about this extremely simple game was the fact that church organisations and the like used to run ‘Beetle Drives’ (like a Whist drive but playing ‘Beetle instead of cards) in church halls and community centres. It was always adults that attended these ‘Beetle Drives’ and as they kept going back week after week I can only assume that they enjoyed themselves. Nowadays, I suppose, we have progressed to the much more exciting game of Bingo (but how artistic can you get just ticking numbers off a card?)!!

Not long after we arrived in Devon, dad met up with Arthur Thair (a builder who used to live at Halsdon Cross on the corner of the Exeter Road and Iona Avenue). Through Arthur Thair dad was introduced to The Loyal Order of Moose. He joined the organisation and became quite an active member. ‘Moose’ was a ‘service’ organisation on similar lines to The Royal Antediluvian Order of Buffaloes, but ‘Moose’ was a Canadian import, whereas the others usually found their base in the United States. Since Arthur Thair had spent a lot of his life in Canada (he may actually have been Canadian), ‘Moose’ became the obvious choice. There appeared to be a Lodge meeting once a week, where I assume dad, and other ‘Mooses’, wined and dined whilst discussing their next fund-raising venture. Once a year ‘Moose’ put on a party for the children of members. This used to be a fairly low key affair. Also, on a once a year basis, there was ‘Ladies Night’. This was the one night of the year when guilt-ridden members of the Lodge (who had abandoned their wives and partners for one night a week for the past year) salved there consciences by putting on a spectacular Dinner and Dance. At my tender age the only thing I knew about Ladies Night was that mum got all dressed up in her evening dress and ‘finery’ (including her fox fur) and dad used to get dressed up as a penguin in his tails and fancy ruffled shirt and bow tie (which seemed to take at least twenty attempts before he finally got it tied to his satisfaction). I used to watch bemused as this metamorphic transformation took place. The ritual was quite lengthy. By the time dad had found his shirt studs, his suspenders, his socks (with the clocks), his patent leather dancing pumps, cummerbund, etc., etc. Mum seemed to sit for ever in front of her dressing table applying make-up, spraying scent and cologne and so on. It seemed to me that the preparation must take twice as long as the actual evening’s entertainment. The Dinner and Dance was usually held at one or other of Exmouth’s better class of hotels (although the only time I ever got invited, many years later, it was held in the Pavilion Ballroom – which was a bit of a come down!). Incidentally I have never discovered whether the members of the Loyal Order of Moose ever raised any money for charitable works, or even if they carried out any charitable works – but I’m sure that they enjoyed themselves.

I notice that there has really been no mention of my younger brother (other than to say when he arrived) in this narrative so far. I am not deliberately ignoring his presence (although before a certain age younger brothers don’t really exist!), but, as he was only twenty-three months old when war broke out, he wasn’t playing a major role in my life. One of the few incidents concerning Brian that I can recall during this period, occurred one winter’s day early in 1939. Brian and I were playing (separately) in the dining room in front of a cosy coal fire. In front of the fire was a tall free-standing fire guard. The guard stood about three feet high and surrounded the tiled area in front of the fireplace. I think that mum was upstairs at the time and dad was outside in his vest and trousers (the temperature was probably just below freezing point) talking to Joe Howes over the garden fence. I was obviously very engrossed in what I was doing – because I certainly didn’t notice what Brian was doing!! My first warning was when I felt that the room had suddenly got considerably warmer. Brian, who had been happily playing with a pile of his soft toys (Wilfrid Rabbit, Mickey Mouse, a large teddy bear and assorted smaller members of his fluffy menagerie), must have become bored. To add a bit of spice to his ‘current game’, my fifteen month old brother had decided to cremate his toys. As it dawned on me that the room temperature was increasing rapidly I discovered to my horror that he had been ( and still was) throwing his toys over the guard into the fireplace. One had actually gone into the fire and had fallen out to ignite the others. I did what any level-headed kid of six and a half would do – I panicked!! I yelled out in my loudest and most raucous ‘coke-hammer’ voice and mum and dad came running – arriving in the dining room simultaneously. Mum grabbed Brian and got him out of the room whilst dad started throwing the burning toys out onto the back lawn. I was quite ‘miffed’ that everybody decided to ignore me! I was not disappointed for long though. As soon as the panic was over and the last of the smouldering toys had been extinguished I got my reward! I received a severe tongue lashing for my failure to keep an eye on what my brother was doing. I silently and sulkily resolved that in future I would say nothing and let the house burn down!

I don’t recall any other potentially major catastrophes in those days, possibly because dad ran a fairly authoritarian regime and we kids had to stay strictly within the rules – and there were plenty of rules to remember. One of dad’s strictest rules was to do with firearms. We had quite an arsenal in the house in those days. There were three hand guns, a German Luger, a service .38 revolver, and an Italian hand gun (which I think was called a Cebra, or a name similar to that). There was also a powerful air pistol, which I hadn’t the strength to reset, and a .22 rifle (which later on was fitted with a telescopic sight). Ammunition for these weapons was hidden all around the house, but I think that I had discovered all of the ‘hiding’ places. The boxes of ammunition used to fascinate me, all neatly stacked in rows with the lead (or nickel) heads of the bullets uppermost. From a very early age dad used to give me instructions about handling weapons, although apart from the air pistol (which he loaded for me), I never actually fired any of the guns. The rules when shooting at a target with the air pistol were as rigid as if I was using one of the other firearms. Always point the pistol towards the ground until you were ready to take aim. Always ensure that everyone was behind you and that there were no objects beyond the target before raising the weapon. Slowly raise the weapon, using both hands, vertically towards the target. Breathe in and slowly release your breath whilst lining up the target. When you have the target clearly in your sights and your hands steady, slowly exert pressure on the trigger. And so on and so on!! Dad was so strict about weapons handling that I remember that on my fourth birthday mum and dad had bought me a ‘cowboy’ outfit. This consisted of a cowboy hat (although it looked much more like a Boy Scout’s hat), a red neckerchief, a small decorated ‘waistcoat’ with a sheriff’s badge on it, lightweight decorated ‘trousers’ with chaparrals, and a gun belt, with holster and imitation ammunition and, of course, an imitation ‘six-shooter’. Needless to say it was the favourite present from the instant I opened the packaging. I got dressed up in all of my regalia (with a bit of help from mum) and ‘moseyed on down to Dodge City’ to clean up the town. As I was moseying dad came round the corner of the house and ‘Dead-Eye Dick’ immediately drew his six gun, pointed it at this approaching bank robber and called out “Stick ’em up!” This challenge was greeted with a swift clip on the ear and the admonition “Never ever point a gun at anyone unless you are prepared to kill them!!” I don’t think that I ever wore that cowboy outfit again and instead went back to making bows and arrows – I reckoned that life as a cowboy was no fun and that it was easier to join the Indians. Later on in life I was encouraged by dad to join him on the rifle range and to use the .22, but, apart from one occasion much later in my life, I always treated guns with a very healthy respect and was doubly careful when handling either the gun or the ammunition.

When we first moved to Devon we were the proud possessors of a genuine ‘Magic Lantern’. Nowadays, as home entertainment, it wouldn’t even rate a mention. It was, as you would expect, a lantern which projected pictures onto a screen (in our case the screen was a table cloth!). It was nothing remotely like a transparency projector for displaying ‘holiday snaps’ – the light source was an acetylene lamp (the acetylene was produced by dripping water onto calcium carbide). The ‘pictures’ to be projected were hand-painted onto glass and from the point of view of a four or five year old boy were of no interest. Adults used to ‘ooh’ and ‘aah’ over the home picture show the first time they were invited to a demonstration, but I don’t recall anyone really becoming addicted to it as a form of entertainment!

Occasionally dad would take mum and I (not always ‘I’) to the theatre in Exeter for one of the musical shows. The ones that I can remember being taken to, but which went right over my head were “No No Nanette”, “Floradora” and “The Belle of New York”. The Belle of New York must have been the last one that I was taken to as it is the only one which had any impact on my memory. We always used to go to the Theatre Royal in Exeter around Christmas time for the annual pantomime, and whilst I think I enjoyed going to them, there was no way that I would take part in any of the ‘communal silly songs’ that everyone else seemed to revel in (especially dad, mum was a little less enthusiastic). The chances of getting me to volunteer to go up on the stage were way below zero, however it was never a problem because the call for volunteers was nearly always followed by a full scale stampede!. I think that witnessing these stampedes would have put an end to any thoughts that I may have had of going on the stage. At the age of seven I had not given any thought at all as to what I would like to be ‘when I grew up’. This is somewhat surprising because it always came into any ‘conversation’ between adults and myself – for some reason they always seemed to be disappointed when I indicated that I had no idea. However, by a process of elimination I was narrowing the field – ‘the stage’ was out! This was reinforced by being taken by dad to see a marionette show at a small theatre in Exeter. I don’t know why dad thought that I would be interested because he knew that I hated Punch and Judy shows (you may think that I am joking, but it really was the ‘violence’ in Punch and Judy that I just couldn’t stand). You could easily pick me out at a ‘Punch and Judy Show’ on the beach (where I had been deposited so that the adults could get a bit of peace or go swimming or whatever) I was the kid who had his back to the kiosk and was watching the sea!

As a young lad, enjoying the summer school holidays and looking forward to his seventh birthday, there seemed to be no reason for this halcyon to be about to end. Aunt Lil was spending some time with us that summer, but Tim wasn’t with her, she had brought her mother (Emma Constable) with her. I didn’t get on too well with Grandma Constable (which was a bit disappointing because she was the only surviving grandparent on either side of the family). I found her to be quite ‘grumpy’ and I think she saw me as a brat! I don’t remember my seventh birthday for any special reason (for example, I didn’t get another cowboy suit!), however it came and went and the next ‘event’ on the calender was to remember what would have been Doris’s fifteenth birthday. On the 3rd of September Aunt Lil and I had gone for a walk along the cliffs at Orcombe Point. I picked up that Aunt Lil was not her usual jolly self, she had a really infectious laugh and it was always fun to be with her, but on this day there was something different, but it was nothing a new seven year old could relate to. All of a sudden Aunt Lil turned to me and said “We are at War!” I had no idea what she was talking about. We hadn’t met up with anyone, she hadn’t been listening to the radio (in those days there were no portable radios). It didn’t make sense to me. After a while we turned around and walked slowly back home. As we went indoors Lil just said to mum “Well?” and mum just nodded her head. Finally I plucked up enough courage to ask what they were talking about and mum told me that at eleven o’clock that morning we had declared war on Germany. It obviously meant a great deal to all of the adults, but to a seven year old it just didn’t register at all. That was all to change….

RESERVE FLEET – PORTSMOUTH

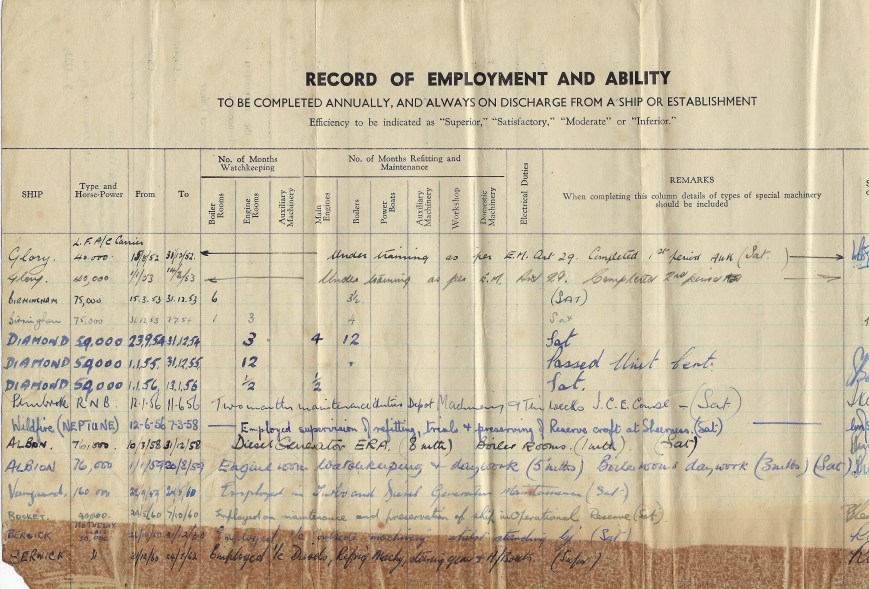

After the Albion the navy took pity on me and decided that an ex-Chatham rating really shouldn’t be given too many big ships – so I got a draft chit to join the Reserve Fleet and was given the Vanguard!! I had a short break when I was sent scurrying up to Buckie to oversee a Coastal Minesweeper under construction on the little slipway there. It had all the makings of a ‘perk’ job. I was boarded out in some sort of Scottish lodging house. Conditions were a little bit primitive but the food was excellent and there was usually somewhere to go in the evenings. I was just beginning to carve out a comfortable existence for myself when some astute pen-pusher checked up on his records and discovered that Hygate had never done the course at Napier’s, so I was recalled to Vanguard. Ah well, you can’t win them all.

THE WAR YEARS

The early days of the war are sometimes referred to as ‘The Phoney War’. For quite a few months nothing seemed to be happening to really effect us in the British Isles. Russia joined in on the side of Germany and helped to ‘carve up’ Poland to their own advantage. The fact that the Communist ‘Bear’ had joined up with the Fascist ‘Eagle’, had many people puzzled. It seemed to be a very ‘unholy’ alliance. Italy had also thrown in its ‘lot’ with its fascist ally. This was more easily understood, Hitler didn’t think that the Italian soldier was a very reliable ally, but he needed the powerful Italian Navy and Airforce to take control of the Mediterranean for him. This meant that Hitler had now got what he needed for his launching pad, the Mediterranean was somewhere he didn’t have to worry about and his pact with Joseph Stalin meant that he could face Europe and his ambitions in that direction without having to worry about his back (not that he had any great respect for the Russian peoples or the Red Army). Now if you think that this seven year old kid had worked all of this out in his tiny mind you are dreaming! War, by and large passed me by, with the occasional inconvenience. The first of these inconveniences occurred fairly early on in the war. One night the air raid sirens sounded. Needless to say I didn’t hear it and the first I new was mum trying to drag me out of bed and to put some warm clothes on me so that we could go downstairs and shelter under the table. I think that mum was ready to give up in exasperation when, having finally got some clothes on me, I then asked if I could now go back to bed. As you can see I wasn’t really into wartime mode at this stage. Fortunately my parents were.

Very early on we had criss-crossed all of our windows with thick brown sticky paper strips (this was supposed to reduced the amount of flying glass from a ‘near miss’). Dad’s next venture was to organise some form of air raid shelter. In this I decided to take a hand and proceeded to dig a deep hole in the back vegetable garden. It was more than a little fortunate for me that there were no vegetables growing at the time. Dad had different ideas for a shelter but graciously informed me that my efforts would not be wasted, ‘as the back garden really needed a good deep turning over and he felt sure that the weeds wouldn’t stand a chance’. Dad’s air raid shelter was ‘different’! He cut a hole about a yard square between the floor joists in the corner of the dining room. He then dug out some of the dirt under the floor, until we had about four feet of head room. He then stocked up with ‘night-light’ candles, matches and put some old linoleum down there to cover the bare earth. It was not luxurious, but the public air raid shelters tended to be pretty disgusting places anyway. The Government were busy trying to talk householders into building ‘Anderson’ shelters in their back (or front) gardens. These were curved pieces of corrugated iron that fitted into a trench (that you dug into your garden to a depth of about four feet deep) and then the outside of the iron was covered with the soil and turf that you had removed for the trench. These had a nasty habit of filling with water when it rained and if you had neglected to bail them out and the siren sounded it was very tempting to take your chances and stay in bed anyway!! The other Government offer was the ‘Morrison’ shelter. This was a substantial steel table with heavy mesh around the four sides to prevent flying debris hitting the occupants. These shelters did not appear until later in the war. To start with all available iron and steel and other metals were being collected for the ‘war effort’.

H.M.S. WILDFIRE – SHEERNESS

Wildfire was a magnificent ‘backwater’ where one could almost forget that one was serving in Her Britannic Majesty’s Grey-funnel Line. We had a three-ringed ‘skipper’ who had no idea of what was going on around him (or his establishment). Naval ‘good order and discipline’ was maintained by a Regulating Petty Officer who was Rationed Ashore and spent as little time as possible on the premises. The Chief Cook was also RA but seemed to cook up some reasonable meals (at least for the Chiefs and Petty Officers Mess – I don’t know how ‘the other half’ fared, although I don’t recall too much in the way of mutinous talk. The daily ‘routine’ was arduous. We would stroll off to our allocated ships sometime around nine in the morning. Have a quick check up on the progress (if any) on the white and pink defect sheets – carefully marking them with the official ‘codes’ – a capital C with a tick through it in the unlikely event of the dockyard actually completing an item of work, or a capital “IH” and the date if you discovered an item that they had finally decided to give some attention to the requirement of the defect list. Most defect lists consisted of a series of “IH”s with dates which stretched further and further back into historical times. Occasionally they did complete an entire white sheet (but I don’t ever recall a pink sheet achieving better than a 50% completion record). My first sweeper was the Calton and had standard Mirlees main engines and pulsing generator. The day the dockyard fired up the main engines for the first time after having completed a top overhaul was quite exciting. They had left a 1¼” whitworth nut on top of one of the pistons on the port main engine. The resulting noise was quite something, but the chargehand insisted that ‘nothing was wrong, they always sound like this!’ I was not taken in by his assurances and moved along the individual cylinder fuel pumps, pushing the control to the maximum fuel position to see if I could isolate the offending piston. I found it!!! When I increased the fuel flow to the appropriate cylinder there was an almighty BANG!!! and the engine covers fell down. I stopped the engines and asked the chargehand if he would like to repeat his comment about the engines always sounding like this. He, believe it or nor, was still unconvinced, until I pointed out the 1″ diameter pushrods on this cylinder literally bent like a dog’s hind leg!! They reluctantly removed the cylinder head to display the ‘carnage’ beneath. Needless to say the “Calton” did not complete her refit on time. During my time at Sheerness I not only picked up refits on Coastal and Inshore Sweepers, I had the dubious honour of being allocated a couple of ‘Gay’ boats. I can remember the Gay Charioteer, but can’t recall the name of the other. The dockyard weren’t happy about having these floating ‘bombs’ in their basin. They were supposed to have ‘gas free’ certificates but the bilges were swimming in Avgas. I was in the engineroom (room not being the operative word) one day when Sparks did something in the switchboard which created a spectacular flash – unfortunately this event was immediately followed by some fuel in the bilges deciding to ignite. I happened to be fairly close to the engineroom ladder at the time but Sparks beat me out (I think I had a set of footprints up the back of my overalls). As I went up the ladder I pulled the releases on all three Methyl-bromide extinguishers. Yep!! You guessed it. Nothing. All three were empty. I grabbed an ordinary extinguisher and like the gormless fool that I am I tried to put out the fire. Fortunately for me there was not a lot of fuel swilling about (and I think that it was probably Pool petrol and not Avgas anyway) and about the same time as I got the extinguisher working the fire had run its course and given up, with only some minor charring to show for all of the excitement. I decided to come up on deck for some fresh air and a cigarette to steady my nerves and discovered to my amazement that the brave fellows of the Dockyard Fire Brigade had cast the MTB adrift and shoved it into the middle of the basin. I was not impressed!! They also decided that every time I was going to run one or more of the engines I had to let the Dockyard Fire Brigade know and I was not to start an engine until they had all of their hoses and equipment ready and gave me the go ahead. I remember that one day I had gone all through this pantomime, received their blessing and duly started up the Starboard RR Merlin. Unfortunately the Dumbflow decided to misbehave, producing quite a loud banging noise which I could hear clearly above the noise of the engine, so I shut the engine down. Apparently the noise outside the engineroom was a little more demonstrative, so much so, that when I came up on deck (inwardly cursing my luck) there was not a sign of any of the fearless firefighters. Their equipment was still there. Slowly heads appeared from behind various ‘shelter points’ until we had a full muster. I thanked them for their concern for my safety and their prompt action in saving their own skins. They packed up their gear and slunk off back to their station ‘muttering darkly’, I was never again to benefit from their invaluable assistance!